Consumption Must Flow

In 1859, Thomas Austin released twenty-four rabbits on his estate in Victoria, Australia. His intention was simple: to establish a population for hunting sport. Within six years, his hunters had killed over 20,000 rabbits. Within a decade, millions hopped across the continent. The rabbits devoured native plants, devastating indigenous species and transforming the landscape. By the 1920s, Australia's rabbit population was estimated at 10 billion—over 1,500 rabbits for every human on the continent.

Feedback loops maintain balance or drive change through the continuous flow of resources and information between parts of a system. In a forest, as vegetation grows, it cools the area by providing shade and releasing moisture, which encourages more growth—a positive feedback loop that amplifies itself. When predators thrive, their population growth reduces prey numbers, which eventually limits predator success, forming a stabilizing negative feedback loop. These mechanisms are fundamental to natural systems. Like Austin's rabbits converting Australia's resources into an overwhelming population explosion, small inputs can transform into dramatic outcomes. The economy itself is such a system, driven by the circulation of value—where production flows to consumption, and consumption sustains production. For the first time in history, the economy's fundamental feedback loop faces breakdown.

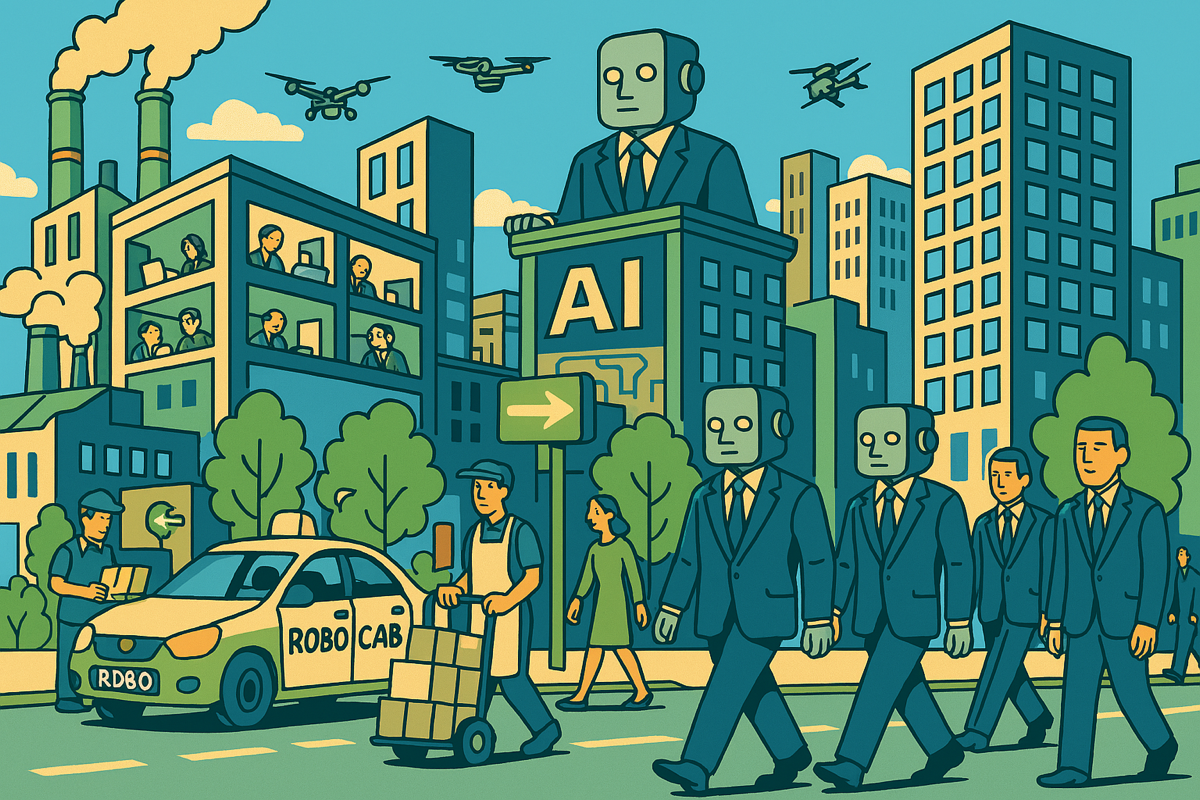

For years, the automation narrative centered on physical labor—factory work, cleaning, construction—assuming cognitive skills would prove more elusive. Instead, disruption is beginning in white-collar domains, with AI systems now matching or exceeding human experts in writing, coding, and legal analysis. Yet a crucial limitation remains: these systems can't be trusted to act independently. The next frontier, reasoning, aims to solve this problem. When machines can verify their own work and correct their mistakes, we'll begin entrusting them with real responsibility.

OpenAI's o-series models, beginning with o1 in late 2024, heralded the start of this paradigm. Their breakthrough in reasoning transforms how AI approaches problems. Instead of pattern matching against training data, these models can dynamically adjust their cognitive effort and methodology—much like a human expert shifting between routine and complex tasks. The recently announced o3, expected in 2025, cemented the promise of this new architecture. They achieved radical gains in benchmarks many believed would remain unsolved for years. These models have demonstrated broad expertise in all human knowledge domains and will cost well below minimum wage, ultimately trending towards the cost of electricity. Take a moment to let those remarkable facts sink in.

The economics are undeniable. These models will enable a single engineer or analyst to accomplish what currently requires teams of specialists, at a fraction of the cost. Their deployment will reshape competitive dynamics across industries—not through sudden disruption, but through steady erosion of the cost structures that define modern business. Organizations that resist adoption will find their margins increasingly difficult to defend against AI-enabled competitors.

Initial adoption will be cautious. Most businesses will start by augmenting their existing workforce, using AI to handle routine tasks while humans maintain oversight. But as these systems prove their reliability, the economic calculus becomes harder to ignore. Each successful implementation will create pressure on competitors, driving a gradual but inexorable shift toward AI-centered operations.

Even as evidence mounts that something unprecedented is occurring, status quo bias will be challenging to overcome. The debate will pit those who see automation as a temporary reshuffling against those who see it as a fundamental shift. Skeptics will have history on their side—after all, predictions of technological unemployment have proven false many times before. The traditional narrative holds that whenever technology displaces jobs, new industries and skillsets emerge to employ even more people. Optimists will point to familiar examples: the advent of personal computing, the internet, and the smartphone revolution. Each of these, they argue, created jobs across the spectrum—from manufacturing and design to logistics and customer support.

Yet AI represents a qualitative change from past technological disruptions. Unlike previous waves that repurposed labor between sectors, AI won't just automate specific tasks—it will replicate core human capabilities. This means that even as new industries and roles emerge, they'll be prime candidates for AI from day one. The migration of work from humans to machines will mirror the outsourcing wave that transformed manufacturing, but with AI offering not just cost savings but superior performance across all knowledge work.

Some economists will dispute this, arguing that comparative advantage still holds—that we wouldn't use a superintelligent AI for basic tasks any more than we'd have Nobel laureates doing data entry. Though understandable, this is an incoherent position—it stems from intuitions about scarcity that have held true for all of human history. The most sophisticated AI systems already routinely handle both complex research tasks and mundane administrative work everyday. While a Nobel laureate must choose between high and low-value uses of their scarce time, AI can be replicated at negligible cost. The economics of scarcity that underpin comparative advantage simply don't apply.

What will endure are roles defined by preference rather than capability—positions where human presence or human origin is specifically valued for its own sake. This includes artisanal goods where human imperfection is part of the appeal, tastemakers and influencers whose quirks and authenticity draw followers, performers whose personhood is core to their art, and luxury experiences where human attention conveys status. But these positions will exist primarily because human involvement is desired, not necessarily because humans perform the tasks better.

We are ultimately facing a breakdown to the fundamental feedback mechanism underpinning market economies: the circulation of wages from production back to consumption. Unlike previous technological shifts that found many new uses for human labor, AI will progressively sever this loop altogether—enabling prodigious productive capacity while destroying the wage flow that generates demand. Wealth then pools at the top, but with no one left to buy, even the wealthiest feel the squeeze as markets shrink. At that point, you either rebuild the loop or face cascading collapse. Most still see AI as just another instance of technological progress, but that is a dire misunderstanding.

Many concerned observers will propose banning or restricting AI to preserve jobs. This approach will likely prove infeasible. Since much of commerce is global, self-imposed bans on development or implementation will cede vast industries to countries that chart a different course. Nations that restrict AI development will watch their innovative firms relocate to more permissive jurisdictions, while their domestic markets are still transformed by AI-powered goods and services flowing in from abroad. Once these technologies demonstrate their value, pressure from businesses and consumers alike will make restrictions politically untenable. We simply cannot suppress a general-purpose technology that delivers radical productivity gains at minimal marginal cost.

As with the COVID-19 crisis, the United States will likely default to quick measures at the onset of an AI-induced downturn—perhaps expanded unemployment benefits or targeted stimulus payments. The Trump administration taking office in 2025, with Elon Musk as a key advisor, will likely face the initial stages of this disruption, perhaps as early as 2026. Despite Musk's deep familiarity with AI technology, their initial response will likely follow traditional economic thinking—treating AI driven unemployment as temporary dislocation that will self-correct over the long term.

For a time, people may move from higher paying professional roles to lower wage service jobs in hospitality or retail, hoping to keep afloat. But even in those industries, automated solutions (like self-checkout, automated customer service chatbots, and self-driving cars) will increasingly take hold. Humans who have lost professional salaries might find themselves competing for gig work that barely covers basic expenses. Consumer spending power in the aggregate then takes a sustained hit, kickstarting a recession.

Once reality sets in that this is a permanent structural change and not merely temporary flux, economists and policymakers will have to consider more radical solutions. The only viable long-term response is some form of broadly available welfare, through either direct transfers or recapitulating make-work programs, last seen during the Great Depression. Universal Basic Income will likely emerge as the leading solution. Traditional welfare programs would struggle to means-test millions of displaced professionals. Job programs may appear dystopian due to the permanence of the situation.

While UBI has been debated on and off for decades in high-income countries, it remained largely theoretical—a solution in search of a problem. The argument in favor of UBI is that instead of tying survival to increasingly automated job markets, individuals would receive a guaranteed stipend. But importantly this policy moves away from moral justifications. This isn't welfare as traditionally conceived. We will be facing a systemic failure of the whole economy that can only be prevented by reconstituting the feedback loop between production and consumption.

Once established, UBI would function similar to baseload power in energy grids. Our electrical system uses stable sources like coal and nuclear to ensure uninterrupted supply, preventing blackouts and supporting critical systems. Likewise, UBI would install a strong base of consumption throughout the economy, maintaining essential economic activity as employment patterns shift. With this foundation secured, the rest of the economy could operate more flexibly and minimize social upheaval and market volatility.

This new economic order would represent the culmination of countless generations of innovation and discovery, from stone tools to nanometer sized semiconductors.Reframing citizens not as the recipients of charity, but as the beneficiaries of humanity's technological inheritance. And like trust fund recipients, people would be free to pursue additional earnings and opportunities, leaving behind the paternalistic constraints of welfare.

The central question quickly becomes how to fund it. Taxation faces both practical and systemic obstacles. Business interests will fiercely resist corporate tax hikes, arguing they stifle innovation and trigger exodus to lower-tax jurisdictions. More fundamentally, as AI drives down human employment, the traditional tax base erodes. This forces ever higher rates on remaining taxpayers, risking capital flight and economic stagnation.

Monetary expansion offers an alternative path. While this possibility stirs fears of inflation and currency crises, automation fundamentally changes the equation. Traditional inflation occurs when money creation outpaces real productive capacity. But AI and robotics will be able to scale up production much more radically than our human labor based intuitions suggest. In principle, monetary expansion could match this increased productive capacity without triggering inflation.

This positions governments as stewards of collective prosperity. Monetary expansion and UBI rates become a dial for abundance, functioning as a signal to our synthetic workforce. Each uptick effectively pre-orders more production across the economy—AI systems see the increased purchasing power and rapidly adjust manufacturing, service delivery, and resource allocation. With software managing everything from supply chains to quality control, production can respond far more quickly to changes in demand than traditional human-managed systems.

This new mechanism fundamentally changes economic cycles. Traditional recessions stemmed from mismatches between production and consumption, where businesses had to guess future demand, stockpile inventory, and slowly adjust to market signals. Workers would lose jobs, reducing consumption, creating a downward spiral that took years to correct. But in an AI-driven economy, the lag between demand and supply shrinks dramatically—synthetic labor can scale operations efficiently, raw materials can be algorithmically sourced and redirected, and production capacity can shift between goods as needed. The business cycle as we know it—boom and bust, inflation and deflation—gives way to something more like a throttle, where output adjusts more fluidly to match consumption.

This transformation would elevate the role of government from economic overseer to active distributor of wealth. Political engagement may rise—not out of ideology, but due to increased relevance. The act of governing gains weight; the outcomes of elections begin to affect day-to-day life. Historically, governments managed economic flows indirectly—through taxes, subsidies, and interest rates. In an AI-dominated economy, this would be replaced by direct distribution. Elections would no longer hinge on abstract promises of growth but on immediate, tangible questions: How much will I receive next year? How much surplus will the government return to me? Perhaps more analogous to a shareholder meeting where dividends are determined. This new responsibility will demand novel frameworks for accountability, lest the state slip into patronage, favoritism, or instability.

The future could be bright, but is not guaranteed. If governments fail to act, the economy risks imploding under the weight of its own success. Without redistribution, AI driven displacement will set in motion a negative feedback loop of decreasing demand culminating in a market collapse; something even the wealthiest will not be able to insulate themselves from. Navigating this transition requires foresight, coordination, and a willingness to abandon economic orthodoxy that has guided societies for centuries.

The challenge ahead is less technical than cultural and institutional. Can governments rewire themselves fast enough? Can democracies handle the responsibility of directly managing income distribution without succumbing to corruption and abuse? Can individuals accept that the nature of work is changing forever and embrace new definitions of human worth and purpose? If managed wisely, the AI-driven economy could usher in an era of shared prosperity unrivaled in human history. The stakes are high and the window for planning brief. This isn’t just a technological transformation—it’s a societal metamorphosis, and our ability to adapt will shape the future of the species.