The Product Lifecycle of Human Labor

The Twitter/X AI subculture is abuzz with discussions of technological unemployment due to recent progress in reasoning models. I laid out my views thoroughly here and here. In this piece, I want to address the main counterarguments to my position. Noah Smith put out his defense of the status quo in 2024 here, and Max Tabarrok’s recent blogpost has been making the rounds on X. They both do a good job representing the best version of the consensus view and I’d like to address their main points here.

As Tabarrok points out, for over two centuries, labor's share of economic output has held remarkably steady at 50-60%. When we look at the labor market of 1800, many tasks have since been automated by machines or software, yet labor's share of output has persisted. While each wave of automation caused temporary disruptions, workers consistently found new roles, and wages continued to track productivity gains. This stability held because machines could only handle narrow tasks, enabling labor to be repurposed.

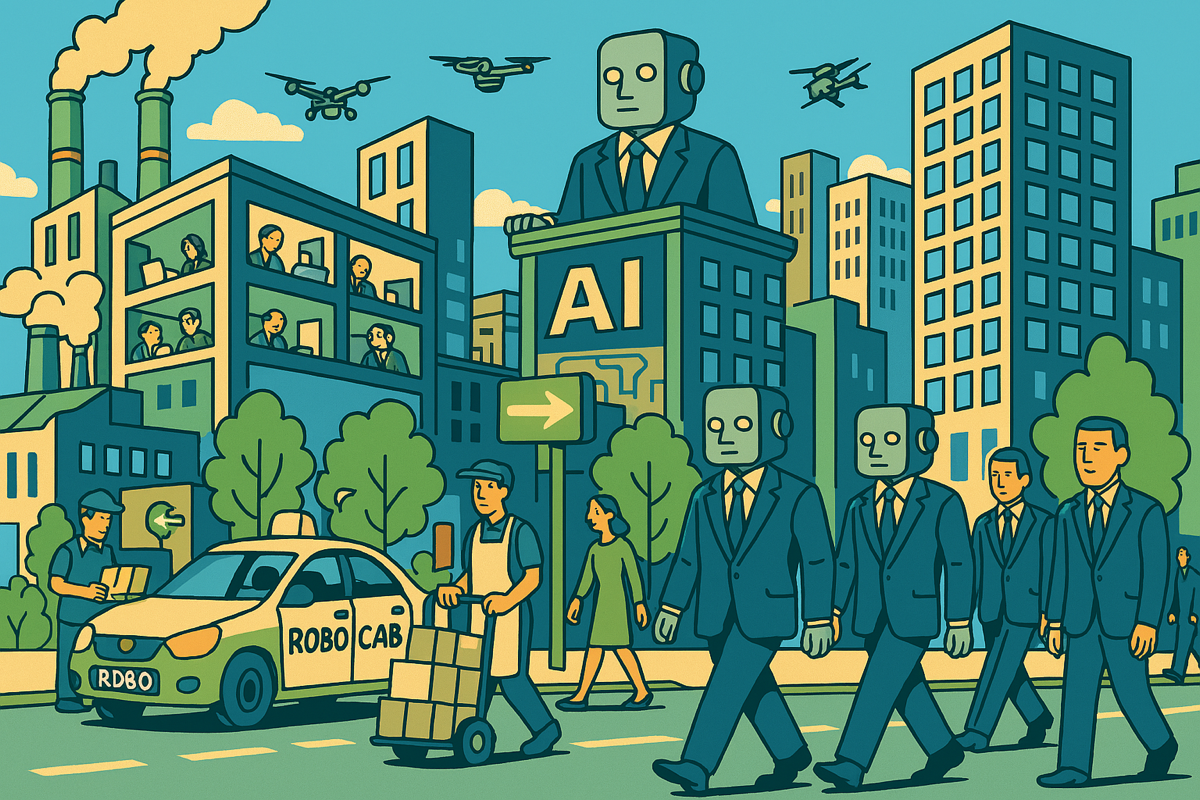

Smith and Tabarrok extend this argument even further—that this same dynamic will apply to artificial general intelligence. That a robot that can do everything better and cheaper than humans will still result in full employment and even rising wages. A bold claim, one that will strike many readers as counterintuitive. After all, previous waves of automation only replaced narrow human abilities. How do we compete with such a robot?

Tabarrok makes his case using population growth as a natural experiment. Human reproduction effectively floods the market every year with over 100 million new intelligent agents. Yet despite competing with more capable workers, less capable workers still find employment. He explains this through opportunity cost: when a brain surgeon makes coffee, they forgo the much higher return of performing surgery. Even though they might make better coffee than a barista, the cost of their time makes specialization efficient. As productivity rises, humanity's expanding desires create enough work for both to specialize in their relative strengths.

From here, Smith emphasizes that AGIs, like highly capable humans, would face constraints that lead to specialization. His key claim is that compute—the processing power needed to run AI systems—would act as a fundamental limiter. While compute capacity continues to grow, it remains finite at any moment, creating opportunity costs. Smith believes these costs would naturally drive AI deployment toward highest-value applications, leaving many economic activities to humans even if AI could technically perform them better. Just as a fast typing venture capitalist may hire a slower typing notetaker to free up time for more valuable work, companies would choose not to use AI for lower-value tasks despite its superior capabilities.

So why question such a seemingly well-supported conclusion? I know of no current polling on this, but it appears that academic economists and social scientists almost uniformly subscribe to this view. But sometimes false consensuses do emerge, and since economics is not an empirical science, it's very possible to make systemic errors, where theory fails to map onto reality.

This debate ultimately centers on the potential for idle resources. Production equipment doesn't self-replicate whereas humans will continue to reproduce even if we have human level robots and artificial intelligence. So the question we're really debating is: is there a scenario where the incentives are such that the human labor resource sits idle? That's certainly never been the case historically. And most economists seem to believe it's almost an impossibility, that it would be in violation of economic physics.

Smith and Tabarrok's argument hinges on opportunity cost and resource constraints, but it conflates two fundamentally different types of scarcity. Human time is a binding constraint—it cannot be duplicated or quickly scaled. Compute, however, is a non-binding constraint; while finite at any given moment, it scales continuously and rapidly to meet demand, operating as effectively unlimited in practice. Software systems are also designed with significant slack resources, ensuring they can handle surges in usage without meaningful limits.

Moreover, they seem to imagine a future with only high-end AI models competing for scarce compute. But the reality is we'll have a range of AI models optimized for different tasks at various price points. This is already the case. These efficient models could end up costing far less than even basic human subsistence—a few thousand dollars per year is quite plausible, where as an American requires around $25,000+ annually just for basic subsistence. At that point, comparative advantage and opportunity cost become largely inert: why hire humans for any task when the AI costs far less and with no meaningful scarcity?

Perhaps most importantly, Smith misuses the concept of opportunity cost to begin with. Appealing to comparative advantage, Smith assumes optimal resource allocation; where actors consistently allocate resources to their highest-value uses. This implies a level of perfect pathfinding that doesn’t align with reality. Behavioral economics has long shown that human decision-making is messy—shaped by emotions, biases, and incomplete information. While Smith presents opportunity cost as an authoritative trump card, it is ultimately a descriptive tool, not a predictive mechanism. It merely restates the obvious: that trade-offs were made, without guaranteeing those trade-offs were optimal or efficient.

This speaks to a broader phenomenon. When faced with artificial general intelligence, there seems to be an instinct to reach for familiar frameworks rather a willingness to think from first principles and verify old axioms. This is a singular event with no direct precedents. We need to be especially careful that our inherited language and concepts are not leading us astray.

Consider the concept of 'labor' itself. This familiar term carries centuries of theoretical baggage: labor markets, wages, employment, comparative advantage, productivity theory. But strip away these vocabulary words and what are we actually describing? Humans are literally general-purpose intelligent systems that can be rented to perform work. We've added layers of theoretical abstraction to what is fundamentally a straightforward service arrangement.

This isn't just semantics. Observe how differently we discuss standard product lifecycles in other contexts. For example, when analyzing semiconductor manufacturing, industry experts discuss the installation base, operating costs, throughput specifications, and migration paths to newer systems. No one debates the "labor market" for older machines or theorizes about their eternal comparative advantage. Managers aren't losing sleep over whether DUV machines will find new roles in the “machine labor market.” These are production tools and they get replaced as better options emerge. The entire process is guided by cost-benefit analysis, capacity needs, and technological fit.

Through the lens of product lifecycle, we can see a simpler reality. Even the most sophisticated production equipment eventually faces obsolescence when better alternatives emerge. Older machines aren't endlessly repurposed. Firms make straightforward calculations about maintenance costs versus upgrade benefits. This arbitrary theoretical category of 'labor' might just be obscuring that we too are production equipment—dominant for a very long time, but not necessarily eternally protected by special laws of economics.

If we remove the academic veneer, the question becomes straightforward: Would a business choose to invest in a human—knowing the associated upkeep, training, management, and retirement costs—if there's an AI system that can produce better outcomes at a lower price? If a company needs contracts reviewed, would they pay a lawyer's hourly rate if AI could handle it better for a few cents? When software needs to be written, would they hire human programmers at $150,000+ per year if AI could produce days worth of code in a couple of minutes for $2400 per year? The empirical data strongly suggests that basic cost benefit analysis drives resource decisions, which suggests that synthetic labor will become dominant.

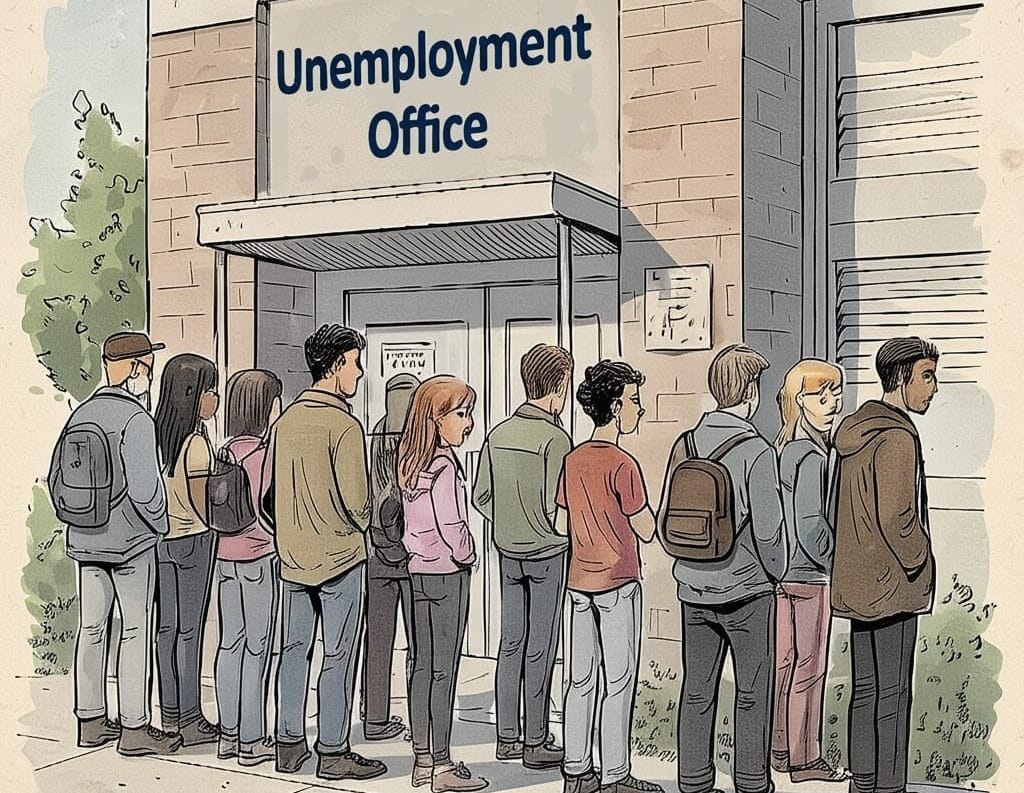

There is an important caveat. Interestingly, both Tabarrok and Smith overlook perhaps the strongest remaining foundation for human employment: the preference for human involvement in certain goods and services. This preference isn't universal, but it plays a significant role in markets where subjective experiences, trust, or perceived authenticity matter. For example, people often prefer human chefs in high-end restaurants, human caregivers for vulnerable populations, or human artists and performers in creative industries. Such preferences could create a durable economic niche for human labor even in a world dominated by more efficient AI systems.

However, this preference is nuanced. For example, robo-taxis and self-checkout systems are rapidly gaining popularity precisely because they eliminate the human element. Many people value the convenience, speed, and reliability of automated systems, especially in situations where human interactions might introduce variability, delays, or discomfort. The same dynamic can be observed in banking apps that replace tellers or digital kiosks in fast food chains. These shifts reflect a growing consumer preference for efficiency over interpersonal connection in certain domains. It's important to keep in mind that there are endless opportunities for social connection in non-commercial contexts.

High supply of displaced workers does not automatically create demand for their services, even in a UBI-supported economy. While UBI could ensure that everyone has disposable income to participate in markets for human-centered goods and services, demand would still depend on whether consumers value human involvement enough to pay a premium for it. We also know that demand tends to be uneven, with a small number of winners crowding out many producers.

The critical question is whether this human preference economy can realistically achieve full employment. This is doubtful in my view. Even with growth in human-centric sectors like caregiving and entertainment, these roles often demand specific skills and talent. Transitioning displaced workers would require substantial reskilling, and not all workers will successfully adapt. Displaced workers from sectors like trucking or manufacturing may lack the aptitude or interest in roles emphasizing interpersonal connection or artistic expression. Societies risk creating bifurcated economies where a minority thrive in high-value niches while a growing underclass faces economic marginalization. While the human preference economy will offer a valuable venue for many, it is unlikely to be a comprehensive solution for mass consumption, necessitating a broader rethinking of the social contract.

These are the kinds of topics that current economic research should be exploring. It's unwise to assume we understand the impact artificial superintelligence and advanced robotics will have on the labor force. Our existing frameworks lack precision and struggle to conceptualize labor as a negotiable form of productive capacity. The typical product lifecycle looks like this: introduction, growth, maturity, decline. We urgently need to understand if we are tipping into the decline stage.

Of course, how quickly this unfolds will depend on AI’s actual progress. Advanced robotics do not exist; superintelligence may be glimpsed but has not yet been reached. A sudden wave of mass unemployment is unlikely. Technological diffusion has historically been a slow process. Bureaucratic inefficiencies and suboptimal decisions permeate the entire economy, at levels. There are plenty of vendors who still don’t take credit cards. But we must acknowledge that human labor being the backbone of the economy is not a law of physics; labor's 60% share of economic output was underpinned by the absence of direct competitors. As that context vanishes, we may face a slow but perpetual increase in the unemployment rate, ultimately leading to a science fiction future where work is fully optional. And that would be a very different world.