The Subtext: You Are A Member of A Colony

Sam Altman recently attended the well-known TED conference and had a sit-down conversation with the host, Chris Anderson. What caught my attention wasn’t any single question, but the vibe of the whole exchange. From the outset, Anderson seemed like someone trying to steady himself—reaching for some assurance that our collective safety is under someone's control.

Altman’s responses, by contrast, are those of someone trying to fulfill an impossible role. But, like the rest of us, he’s just flying by the seat of his pants. Strip away the mystique of power, and he’s a 39-year-old American entrepreneur born in 1985—a millennial who dropped out of Stanford after two years to start a small, ultimately unsuccessful company. Though an important figure, he’s still a young man who happened to be in the right place at the right time, with the right connections and aptitudes. His journey from running Y Combinator to becoming OpenAI’s CEO wasn’t guided by some divine insight into humanity’s technological destiny. In fact, OpenAI itself started as somewhat of a lark:

On May 25, 2015, at 9:10 PM, Sam Altman wrote to Elon Musk:

Been thinking a lot about whether it’s possible to stop humanity from developing AI. I think the answer is almost definitely not. If it’s going to happen anyway, it seems like it would be good for someone other than Google to do it first.

Any thoughts on whether it would be good for YC to start a Manhattan Project for AI? My sense is we could get many of the top ~50 to work on it, and we could structure it so that the tech belongs to the world via some sort of nonprofit but the people working on it get startup-like compensation if it works. Obviously we’d comply with/aggressively support all regulation.

Sam

Sam Altman does not know where this is all going—none of us do. This is a once in a species, epochal change. As the demands on his time and attention increase with OpenAI's success, Altman's capacity for reflection only diminishes. The same is true for every tech leader we place on pedestals. Our society stands at the threshold of profound transformation. It's only an illusion that our leaders comprehend what's coming. Our seeking is in vain.

Anderson, on the other hand, represents an older generation grappling with technological acceleration. At 67, the British-born curator of TED has spent decades as a technology optimist, believing in human ingenuity to solve our greatest challenges. His demeanor throughout the interview communicates what many of us feel: instinctually sensing the danger of unleashing such a power, yet finding no levers to halt the process.

This feeling isn't unique to the AI era, though it brings it to the forefront intensely.

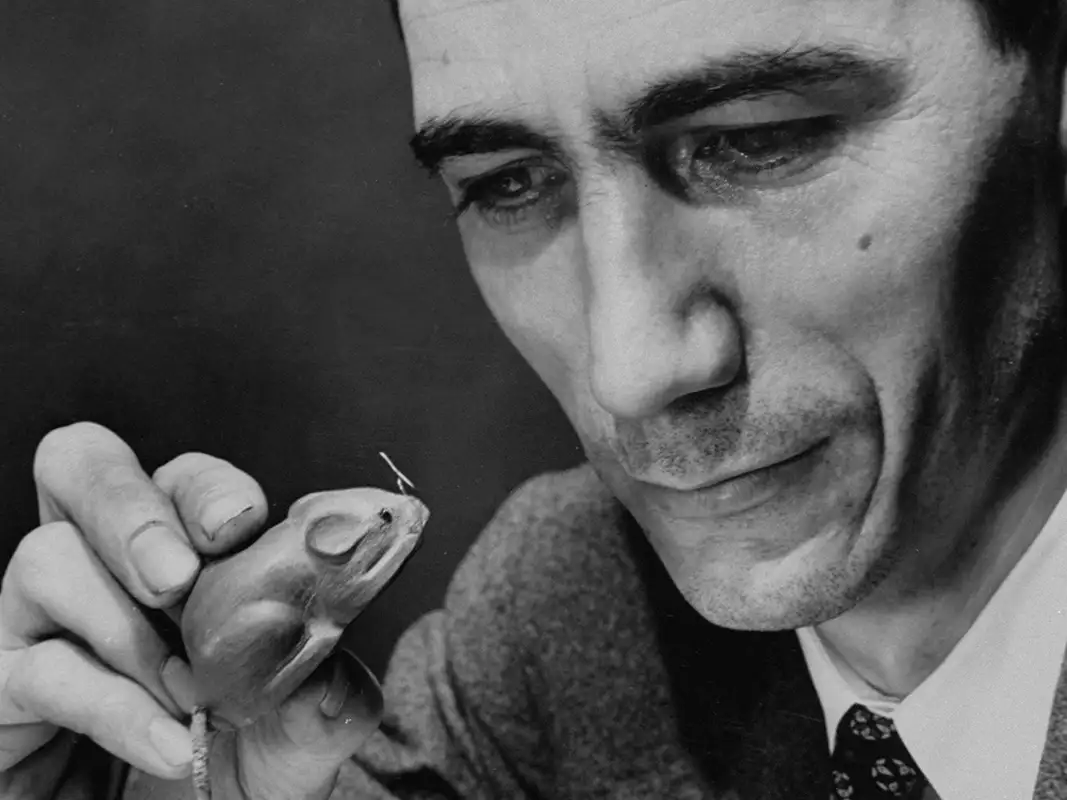

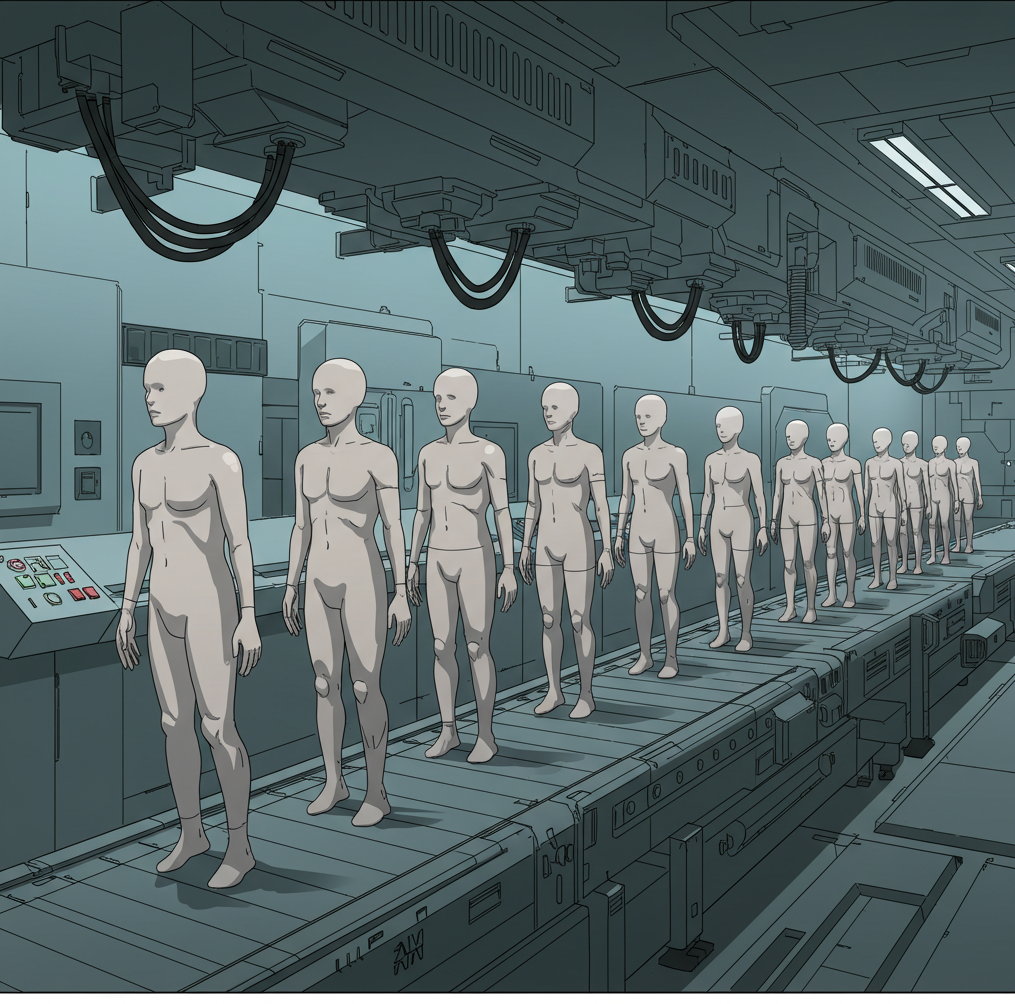

The entomologist E.O. Wilson spent decades studying ant colonies, where no individual—not even the queen—truly governs the whole. A colony’s behavior emerges from countless tiny interactions, producing complex adaptations that no single ant comprehends or directs. Humans, too, are a colonial species, forming what Wilson called a “superorganism.” Our growing awareness of this reality produces an anxiety—the recognition of our group lurching forward with great speed and power while we remain mostly helpless. A straightjacket, straps tight, eyes peeled back. We watch our fate unfold like a TV show, more passenger than participant. Our society accelerates in directions none of us chose, with consequences we cannot fully predict, but must endure.

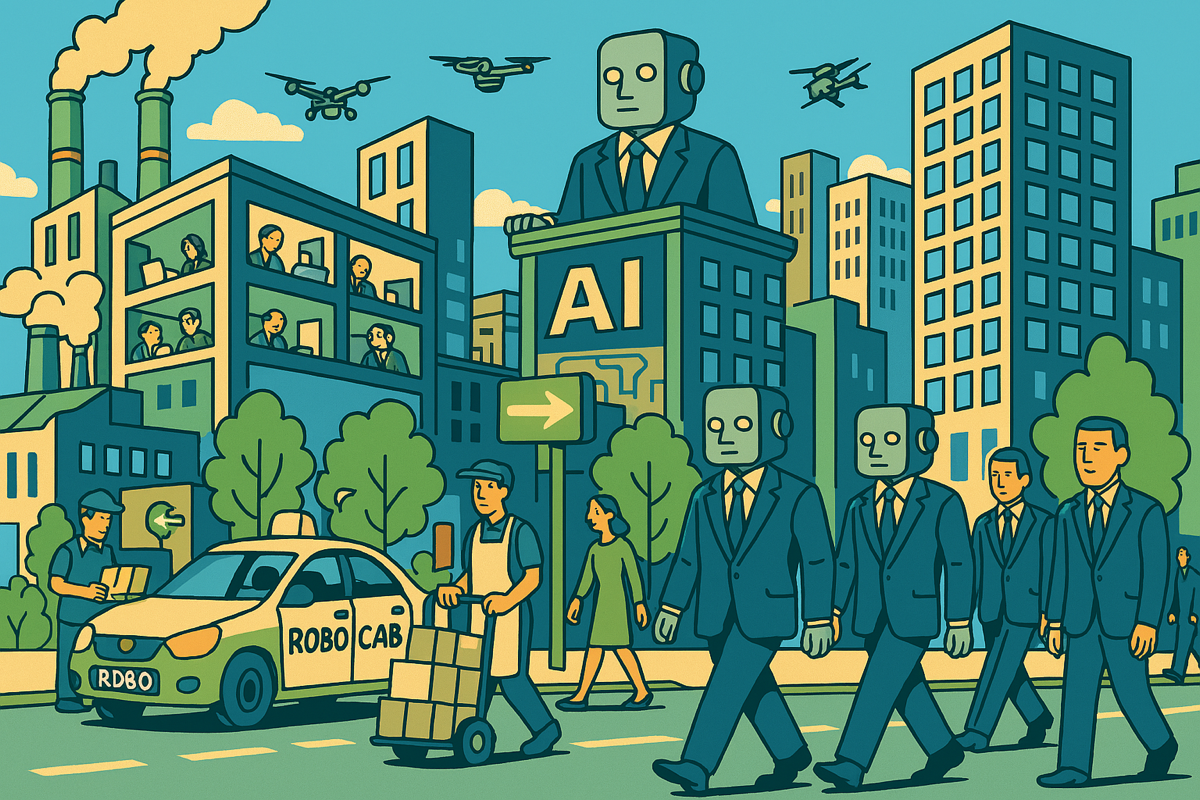

The forces at play are best understood in economic and ecological terms—feedback loops of incentives acting on countless agents. In AI, the dynamic is clear: investors chase returns, labs compete for talent, companies fear obsolescence, and nations seek strategic advantage. Each actor behaves rationally in context, yet together they generate runaway acceleration. This is why appeals to caution often fail—systemic pressures punish hesitation and reward speed. What Anderson seeks from Altman is someone who can override these forces. But as Altman's email highlights so clearly, he too, is but a passenger—albeit an influential one—but still a small part of a grand system whose trajectory is beyond individual intent.

Personifying complex systems may actually impede what little agency we do have. By fixating on figures like Sam Altman, we overlook the small levers that influence the whole: economic incentives, regulatory frameworks, culture, and competitive game dynamics.

Despite the daunting scale, distributed agency is not a myth. Consider the butterfly effect—a concept introduced by meteorologist Edward Lorenz in the 1960s when he discovered that small rounding errors in weather simulations could produce dramatically different forecasts. Outcomes cannot be precisely determined, yet small distributed action can shape a system. It’s harder to recognize and slow to manifest.

What we can realistically do is: our part. Be role players. We can help shift the zeitgeist—away from heroes and scapegoats, towards the truth of colonial life. That we are a collective beast. Each of us occupies a node in the colony: capable of nudging, signaling, organizing, and supporting institutions that shape the whole. If we have the means, we can fund researchers, journalists, and civil society organizations. We make a difference in our local spheres of influence. This very magazine is an attempt at just that.

So yes, no one is steering this ship—but that doesn’t mean we’re completely adrift. This moment demands we acknowledge our collective nature and begin to think like the colony we are.