The Twilight of Labor

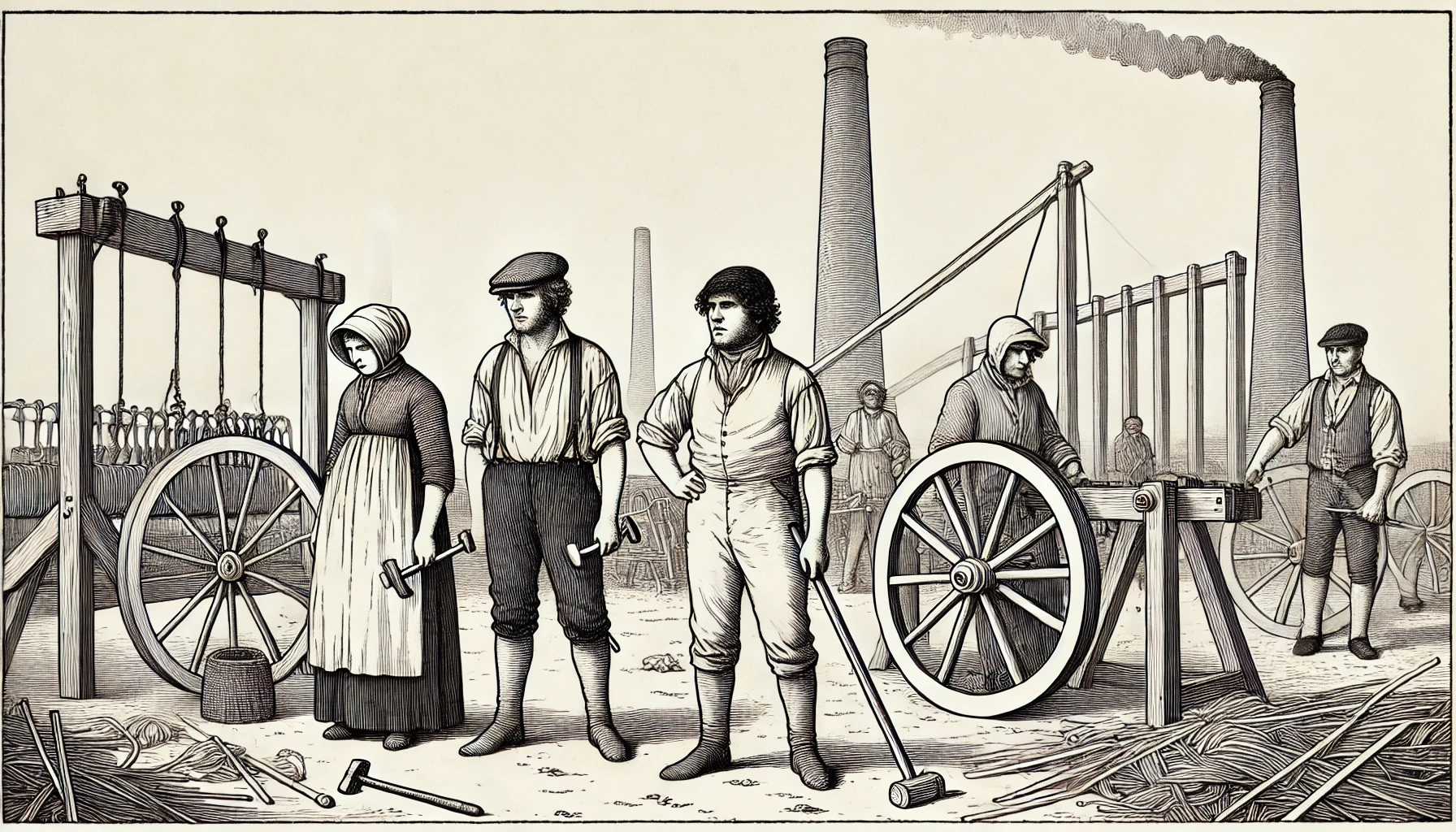

In the dark hours before dawn on April 11, 1812, the sound of dozens of boots crunching on gravel broke the silence around Rawfolds Mill in Yorkshire. William Cartwright, the mill owner, had been expecting them. For weeks, bands of skilled craftsmen turned midnight raiders had been systematically destroying the power looms across England's industrial heartland. Around 150 men approached his mill, their faces blackened with soot, carrying hammers, axes, and primitive firearms.

The Luddites, as they called themselves, were skilled textile workers whose entire way of life was being undone by these new machines. Inside the mill, the power looms stood silent, mechanical frames that could do the work of six skilled men. Cartwright had prepared for this moment, fortifying the mill's windows and stationing armed guards. The first shots pierced the night air. By dawn, two Luddites lay dead, and the others had melted back into the countryside, leaving the machines untouched. The uprising would continue, but the writing was on the wall—no amount of sabotage could hold back the tide of industrialization.

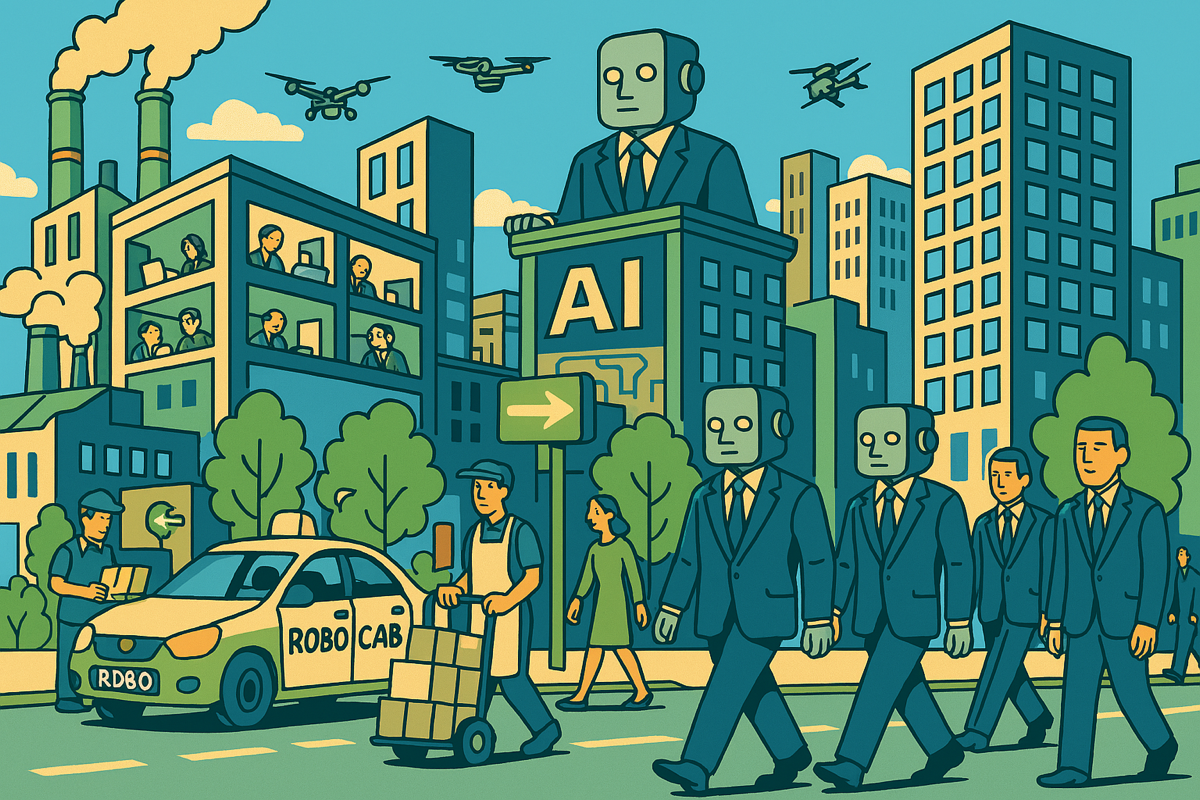

Two centuries later, we face another technological revolution that threatens to reshape the nature of human work. While the Luddites fought against machines that amplified physical labor, today's artificial intelligence systems are automating our ability to think, create, and reason. The fears that drove those Yorkshire craftsmen to take up arms have surfaced once again.

Historically, alarmists have been wrong. The prominent Depression-era economist John Maynard Keynes famously predicted part-time work would be the norm by the early 2000s. In the 1960s a group of scientists and technologists wrote Lyndon Johnson, warning him of the growing threat of “cybernetics.” But as the years went by, new industries kept popping up, creating new fields of work that offset the ones usurped by ever-evolving machinery. Apart from the Great Depression, employment has been robust throughout the 20th century, so the argument has been largely viewed as discredited.

The rapid progress in AI over the past two years has compelled even skeptics to reconsider their views on technological unemployment. Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has been unusually blunt in voicing his concerns. Yet most economists remain unconvinced. If technology is driving widespread displacement, we should see clear signs in the data—radically increased productivity or otherwise inexplicable unemployment. So far, the numbers do not bear this out.

Economists argue that concerns about technological unemployment are rooted in the Luddite fallacy. The Luddites mistakenly viewed the amount of work needed in an economy as fixed—a finite pie to be divided between humans and machines. But history shows this reasoning is flawed. New technologies have consistently enabled entirely new industries and forms of work. Mid-century typesetters couldn't have envisioned their grandchildren becoming search engine optimizers or social media marketers.

The consensus view has its merits, but it’s important to acknowledge that there is no mechanistic basis for this belief. The premise that humans will always be demanded in the production process is based solely on precedent. Some economists may argue that they do understand the mechanisms, but since economists can’t readily do controlled experiments on the macro economy, they are stuck in the purgatory of unverified theory, analogous to theoretical physics without experimental physics.

Economists are correct regarding the Luddite fallacy, but their rebuttal is ultimately the right answer to the wrong question. The risk is not that new jobs will stop being created. The risk is that artificial intelligence is not just taking jobs, it’s replicating human capacities—the true means of production. Demand for labor may not be finite, but the human capacity to do work is. Our bodies and minds are not limitless in ability. We cannot dig like a backhoe or calculate like a calculator. And technologists are aiming directly at our most basic abilities.

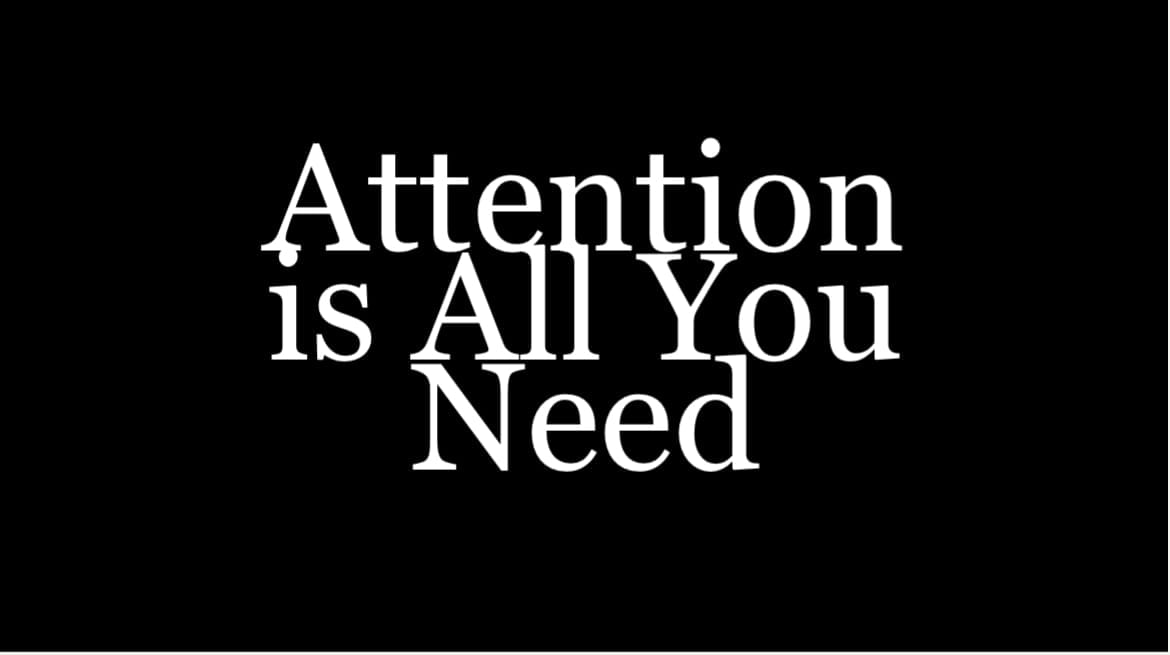

It's easy to forget that ChatGPT is only two years old. Before its arrival, natural conversation with computers was impossible. Now it's routine. Models can generate sophisticated paintings in seconds—work that would take skilled artists days or weeks. They match or exceed human ability in conversation and image understanding. They can even produce film clips that surpass Pixar-level animation in seconds.

OpenAI's new reasoning model, which spends time thinking before answering, already ranks in the 89th percentile on competitive programming challenges. It surpasses PhD-level accuracy on physics, biology, and chemistry benchmarks. These models are rapidly improving with no end in sight. The challenge now is finding what they can't do.

It's important to keep in mind that businesses do not optimize for maximum employment of humans; they optimize for the interests of those who own and control them. There's no unbreakable agreement towards using humans to produce goods and services. We are a means to an end, from a business's point of view. This is why Amazon warehouses have gradually become sparsely populated. As better options arise, market forces lead to adoption in order to survive and win.

Economists generally agree that artificial intelligence will lead to displacement. But the consensus still believes this will be largely short-term, and that over time, humans will adapt. They'll become more productive using these models and focus more on soft skills like creativity and taste. Humans sometimes prefer to interface with other humans—like the hostess at a restaurant or your real estate agent guiding you through a big purchase. To have the actual human touch, you have to be human. There will also undoubtedly be new occupational categories that prove difficult to predict in advance, as life coaches and influencers once were. As the population ages, demand for nurses and caregivers will also grow, and it's unlikely that robots will be ready to fill the void anytime soon.

This is all true, yet none of it changes the fact that whole categories of fundamental human capacities are being imbued in machines for the first time in history. No technology has been general and flexible like this. This is genuinely new. 100% unemployment isn't being debated here, nor is it assumed that massive labor force changes will occur overnight. But we aren't going to sprout new labor organs. Once AI masters one of our domains, that territory is taken. The models will become ever cheaper and ever more capable, indefinitely. It’s not realistic to assume that the median worker will just pivot to AI empowered hustler-entrepreneur, whilst we maintain 3% unemployment.

This isn't temporary displacement; for many, it will be permanent technological unemployment. It will be hard to find anyone who needs your help. This could be as true for highly paid professionals as for low-skilled office workers. All of the tech giants are beginning to realize that what they now must sell isn't software applications, it's synthetic labor. This is essentially turning the software you use at work against you. Photoshop does the paintings and emails it to the boss for revisions. Excel does the data science and sends the reports. The code editor writes the code and ships it. Highly paid and highly skilled jobs are right in the crosshairs.

I believe the tendency to dismiss technological unemployment out of hand has deeper roots than simple oversight. I believe it stems from a psychological orientation I'll call the Ptolemaic bias: believing something chiefly because it elevates human importance. The namesake example is assuming the sun must orbit the earth, not the other way around. Our default view bends to fit our ego. This same tendency warps how we see our role in production. We implicitly believe we are irreplaceable.

But like egocentric illusions of the past, this belief is plainly false. Humans are not essential to most goods and services people demand. We're just one worker in the possibility space of workers. The linguistic division of "capital" and "labor" further obscures this truth. We don't like to group ourselves with lifeless machinery, just as we resist seeing ourselves as merely another animal. We are "people," we are "laborers." But machines and humans are both mechanisms that do work—there is no crucial difference. We might even view living organisms as "natural technology." And as iPhone iterations demonstrate, no technology is final. Technology is generational; improved and sometimes discarded entirely, as happened with horses. Another natural technology whose best days are behind it.

There is a farcical element to this debate. We would never assume some other component of production must be eternal; that we'll always find new uses for Cisco routers or horseshoes. It's not serious. It stems from brains and institutions littered with category errors. The default hypothesis should be flipped—the costs of being caught off guard are too high. We should assume we are headed for a significant increase in structural unemployment with all the accompanying problems. We need rigorous scenario planning, and crucially, people need time to process these ideas.

The economics profession's relative silence on artificial intelligence is vexing. And may be remembered as one of the great intellectual failures in history. The winds of change are blowing. We're facing potentially the most significant transformation of labor markets ever, and our economic institutions offer little more than recycled analyses of the Industrial Revolution and platitudes about human exceptionalism.

Where are the economic models for cognitive expertise that scales at zero marginal cost? Where is the analysis of labor unbound from incentives? Is it dangerous for superintelligences to compete against each other in business? If it is dangerous, can a cooperative market still preserve quality and choice with such non-human entities? These are a few of many pressing research questions.

The stakes are too high for such passivity and incuriosity. $300,000 degrees continue to be purchased. Is warning needed? It's baffling that individual ambition hasn't propelled more fresh ideas or contrarian conclusions. From the outside this appears highly dysfunctional. Perhaps a culture of taboo and timidity has taken hold. Their journals fill with increasingly abstruse refinements of models built for a rapidly vanishing world. The field that produced The Wealth of Nations is too meek to even participate. A shell of its former excellence.

This is more than an academic failure; it's a societal one. We urgently need new thinking to navigate the transition ahead. New social contracts will be necessary. We need politicians with foresight proposing big ideas. Universal basic income, once a fringe idea, becomes almost inevitable. But that's just the start. Our education system prepares people for careers. Our social status hierarchies are largely built around professional achievement. What happens if these foundational structures become obsolete? We can cling to failing systems and outdated narratives, or we can begin the difficult work of reimagining society for an age of synthetic labor.

For thousands of years, labor has been the bedrock of our existence. Countless souls had no choice but to labor. Every steel beam in our skyscrapers, every stone in our cathedrals, every mile of railroad track bears these invisible fingerprints. We now stand at the precipice of a world where the ancient bargain between animal effort and survival may be severed.

This metamorphosis cannot be halted, nor should we wish it to be. Just as the Luddites could not hold back the machinery of progress at Rawfolds Mill, we cannot arrest this transformation. The material abundance possible with artificial intelligence is hard to fathom, and is no fantasy. The cost of synthetic labor will trend towards zero, and this elemental technology will spread to all corners of the world, marking the true end of human poverty. Perhaps this was always the destination. Each generation's effort building the antecedents of a certain type of freedom. Maybe this is not the extinction of work but its ultimate fulfillment—the final inheritance of every callused hand and bent back that carried humanity forward.

Ilya Sutskever, the renowned OpenAI scientist, reportedly implored his colleagues to “feel the AGI,” even leading chants at company parties. I think Sutskever wanted people to engage with the gravity of AGI before it arrived, to move beyond the abstraction and grapple with the true power of what we’re unleashing. Dear reader, feel the AGI.

{This is an updated version of a 2018 essay published in Areo Magazine}