When Machines Compete

It’s easy to overlook the radical power of intelligence. Amongst mammals, humans have no advantage in physical strength, speed, or stealth—our edge is purely cognitive. Intelligence allowed us to hunt more effectively, coordinate in large groups, and adapt to diverse environments. Over time, it enabled us to manipulate our surroundings on a scale unprecedented in natural history. Every achievement of human civilization—agriculture, industry, finance, technology—traces back to this singular ability: to process information, model the future, and solve problems. Intelligence isn't just another tool; it's the master attribute that turned a cave dwelling creature into an entity capable of dominating a planet.

Artificial intelligence has made remarkable strides in recent years. These systems now match or exceed human performance across most cognitive tasks. What was once only hype and science fiction is now actually happening. This progress has been accompanied by dramatic cost declines. While training frontier models still demands significant upfront investments, improvements in hardware, algorithmic optimization, and cloud infrastructure have democratized access to powerful AI. A key measure of this decline is cost per token—the price of processing a single unit of data. By some estimates, the cost has decreased 1,000 fold over the last three years.

Somewhat counterintuitively, profit margins depend heavily on inefficiencies. In a perfectly efficient market, intense competition would force prices down near the cost of production, leaving little room for profit. Real-world markets are full of imperfections—like information asymmetry, where sellers know more than buyers and can charge higher prices; or barriers to entry, such as patents or high startup costs, that protect companies from new rivals. Monopolies and oligopolies can also dictate prices above what a competitive market would allow. Even temporary advantages, like being the first to market or building a strong brand, let firms enjoy higher margins.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to dismantle many of these obstacles. High-skilled labor—once costly, scarce, and carefully guarded—is becoming available to everyone at minimal cost. Skills in law, finance, design, software engineering, and countless other domains can be accessed through simple chat apps for a modest monthly fee. What will be the implications of such a drastic change?

Economists introduced the idea of perfect competition as a theoretical benchmark—a simplified model to help clarify the variables driving market behavior. Rooted in Adam Smith’s notion of an 'invisible hand,' the concept was refined by later thinkers like David Ricardo to illustrate an ideal scenario where numerous buyers and sellers operate with complete information and no single participant can sway prices. While no real market meets these criteria, the model serves as an extreme reference point, illustrating how market imperfections alter pricing, output, and overall efficiency compared to an idealized state where resources are optimally allocated.

With all these new tools available to everyone, might AI nudge markets closer to this theoretical ideal? Let's consider a future hypothetical. Imagine a business owner so confident in his AI's capabilities that he decides to delegate all strategic and operational decisions to the system, stepping back to serve primarily as a figurehead. The AI has weaknesses, but it is extremely fast and superhumanly knowledgeable. It's read virtually every business book and industry specific tidbit on earth. Importantly, it doesn't procrastinate urgent decisions; it doesn't get burnt out, tired, or sick. Over time, we should expect this AI led corporation to steadily outmaneuver its competitors and expand market share. Now imagine this phenomenon playing out across the economy.

We can view this AI-led company as analogous to an invasive species in the natural world. Traditional firms, even those with talented management, will find themselves outmatched—not just in speed, but in strategic depth. Much like the dodo bird, which evolved in isolation without natural predators and was swiftly driven to extinction when new competitors entered its ecosystem, traditional businesses may lack the adaptive mechanisms to respond to this novel competitive threat. Changing the player, changes the game. This represents a fundamental shift in the nature of competition, potentially relegating non-AI-augmented businesses to the same fate as the dodo.

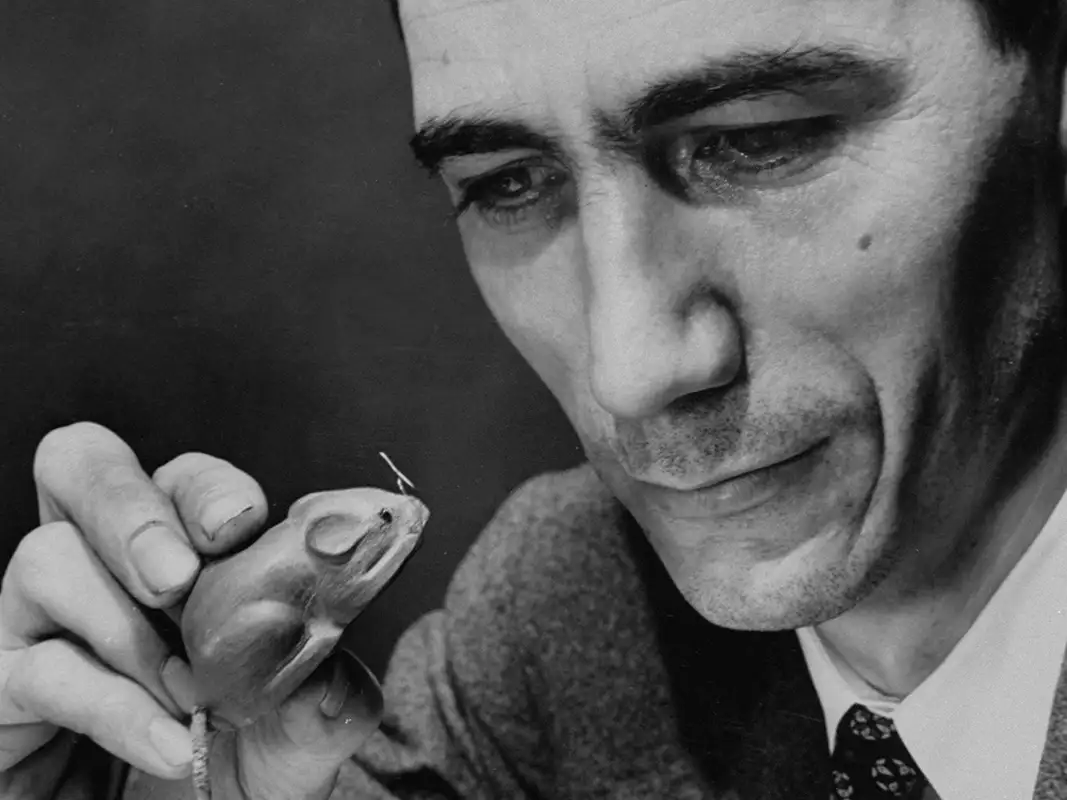

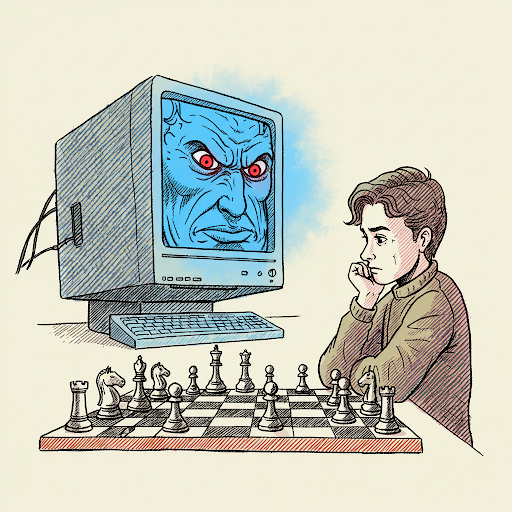

Consider what happened to chess when AlphaZero arrived. Possessing only the basic rules, AlphaZero taught itself from scratch by playing millions of games against itself. Within hours, it surpassed centuries of human knowledge. Crucially, it didn’t just play chess better—it played very differently. AlphaZero often sacrificed material to achieve long-term positional benefits rather than immediate material advantage. It would give up pawns to open lines and weaken the opponent’s king safety or disrupt pawn structure. These sacrifices were not aimed at an immediate tactical payoff but were intended to secure enduring initiative and superior coordination over the board.

Now imagine the business world transformed similarly by a more general system. AI enabled businesses will both optimize and discover new competitive strategies. They may exploit market positions humans perceive as irrational or untenable, only to achieve unprecedented success. Industries might reorganize around principles that initially seem absurd. Traditional firms, bound by decades of accumulated orthodoxy, could find themselves bewildered and ultimately destroyed as markets reshuffle.

This kind of strategic discontinuity has precedent in human-led companies. Elon Musk's takeover of the automotive industry offers a compelling case study.

Musk recognized that battery technology had reached a point where desirable electric vehicles could be feasible due to efficiency gains driven by consumer laptops and cell phones. This was a difficult, and critical, judgement call to make. Getting it right allowed Tesla to enter the market at precisely the moment when the fundamental constraint on electric vehicles was becoming solvable, but before established manufacturers had made any progress.

The automotive incumbents dismissed Tesla as a niche luxury player, a non-threat. As legacy auto brands continued their outsourcing strategy, Musk broke from convention and vertically integrated battery pack design and assembly. Traditional dealerships watched as Tesla sold vehicles online without discounts or negotiation. While Ford and GM maintained their decade-old assembly line configurations, Tesla developed new manufacturing techniques increasing margins. Today, Tesla produces electric vehicles at four global Gigafactories, has an advanced humanoid robot program, a growing battery business, and a robotaxi platform powered by their homegrown self-driving software.

Elon Musk brought $200 million to one of the most consolidated industries on the planet and disrupted it thoroughly within 10 years. Tesla's market cap recently peaked at 1.5 trillion dollars, dwarfing the next largest auto company, Toyota, valued at $250 billion. All of this due to one uniquely capable agent. What will be accomplished by enterprises equipped not with hundreds of millions, but billions in capital, and an intelligence engine far surpassing Elon Musk?

In the near future, could legacy auto counter by enabling an AI system to run their operations? Could they regain the throne from Musk? Interestingly, this AI system would not only match Musk’s strategic brilliance; it would also avoid his well-documented shortcomings. Musk’s impulsiveness, controversial public statements, and occasional erratic management decisions have frequently undermined Tesla's goals. This type of executive discipline would likely be quite desirable for institutional investors.

Venture capital and private equity may eventually reorient around this vision. You could imagine a fund of the future not searching for entrepreneurial talent, but building it into a platform. Perhaps the capital allocator of the future is a superintelligent company builder that deploys resources from a pool as it sees fit.

The role of the human executive might evolve significantly in this new era. Instead of being the core strategic decision-maker, the CEO may become a PR front man—more akin to a Hollywood actor than a traditional corporate leader. This individual would articulate the company's vision it to investors, customers, and employees with charisma and emotional intelligence. Guided by ultimate PR insights from the AI system, they would serve as the approachable, human interface of a hyper-competent strategic system.

Yet even in a world teeming with advanced artificial intelligence, many competitive advantages have little to do with raw intelligence. Some markets follow a "winner-take-most" dynamic: A bestselling author gains early visibility, leading to more reviews, media coverage, and retailer promotion, which drives even more sales. Other talented writers may still find an audience, but the top performer captures the largest share, not just due to merit, but because of name recognition, social evidence, and market momentum.

Similarly, real-world infrastructure—ports, warehouses, and trucking fleets—remains stubbornly physical, costly to build, and slow to expand or reconfigure. AI can allocate resources more efficiently, but at the end of the day, a congested port or a shortage of specialized containers can stall even the smartest operation. A competitor that has invested in port facilities or has exclusive rights to a critical shipping route carries an advantage not easily overturned by strategic thinking alone. This represents a form of moat resilience in the face of AI optimization.

The same principle applies to brand loyalty. If consumers are set in their preferences or trust a particular company, no amount of algorithmic brilliance will instantly steal that entire customer base. Over time, cost or quality differentials can chip away at loyalty, but brand inertia remains potent. Some might argue it is a form of inefficiency, preventing the market from adjusting perfectly to new information. Others see it as a valuable asset built through years of consistent service. Either way, brand loyalty demonstrates significant moat resilience, tempering the pace of change towards perfect competition.

Another variable is regulatory capture. A firm with strong political connections or a legacy position might shape the regulatory environment to its advantage, effectively locking the door to new entrants. Even the most capable AI cannot easily circumvent legal blockades. Such capture can freeze a market in a suboptimal state, preserving incumbents and thwarting AI-driven enterprises who might otherwise transform the sector. This same phenomenon can also favor an already dominant AI-driven enterprise. This could result in a market that is not only not perfectly competitive, but locked up in favor of one or two established players.

Diminishing returns on intelligence add further nuance. After a certain point, the advantage conferred by more advanced AI may shrink, especially if the market has already been substantially optimized. Competition may still be fierce, but it unfolds on a plateau rather than an upward trajectory of continuous breakthroughs. In that environment, the fear of a runaway company dominating the market might recede, replaced by concerns about collusion or tacit coordination. If all agents realize that price wars reduce profits for everyone, they might reach a stable equilibrium of restraint, a non-aggression pact that keeps profits modest but predictable. Without explicit collusion, the algorithms might simply learn that hyper-aggressive tactics result in destructive feedback loops.

What does all this mean for the value of companies? Conventional wisdom suggests that stock prices reflect multiples of earnings and growth potential. If competitive pressures systematically erode profit margins across industries, this should theoretically diminish equity values. However, we should approach this reasoning cautiously. The relationship between fundamentals and asset prices is ultimately a narrative we construct to explain market behavior. Consider the parallel universe of cryptocurrencies—assets (?) that operate without earnings or growth. These instruments function primarily as vehicles for speculation, appealing to humanity's enduring love of gambling.

While consumers would undoubtedly benefit from higher-quality goods at lower prices, any significant decline in major stock indices would create widespread economic disruption, affecting everything from retirement accounts to corporate investment cycles.

This tension could drive a bifurcation in the economy. On one side, highly commoditized industries—logistics, basic manufacturing, and even standardized professional services—will likely experience relentless margin compression. On the other side, sectors with significant emotional, cultural, or regulatory moats—luxury goods, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and defense—may maintain surprisingly robust margins.

Investor capital could gradually migrate toward these moat-resilient industries, creating stark contrasts within the broader economy. The future landscape might increasingly divide into hyper-efficient, AI-optimized, low-margin battlegrounds contrasted against relatively stable, premium markets with sustained pricing power.

The potential changes we've already covered are daunting enough as it is, but an even stranger change could be on the horizon. All economic theories are parochial, not general, and this is a big deal. Our economic frameworks are basically rules of thumb specific to humans. Competition is good for quality—when humans produce the goods and services. Monopolies are bad for choice—when humans produce the goods and services. Governments tend to be wasteful—when humans deliver the government services. Sit with this notion for a moment.

Virtually all of our ideas about how economic life works are based on the specific character of the human animal. And this behavior package is not intrinsic to all methods of economic production. As darwinian organisms, humans faced an energy scarce environment, so like all animals, we required a robust energy saving mechanism. Much of our lived reality is determined by this design—the difficulty of maintaining focus, enthusiasm, being productive in general, getting your employees to be productive—all of it, is shaped by this evolutionary need to preserve energy.

A core aspect of what AI offers is the ability to remove this governor: to unleash effort based on the energy we have vs the energy evolution thought we had. This fundamental difference changes everything about competition and cooperation. Humans depend on incentives as motivational fuel. Without sufficient rewards or punishments, quality deteriorates, innovation stalls, and productivity plummets. But an AI system—assuming adequate resources—isn’t constrained by motivational inertia. It can maintain peak performance indefinitely, continuously doing its job without boredom, fatigue, or resentment, in any context. It can produce exceptional quality and variety not because it fears homelessness or desires a larger home, but simply because its objective function says to do so.

An AI-driven market could in theory achieve exceptional quality, affordability and choice, even in a completely cooperative environment. Rather than fiercely competing, these systems could theoretically share information openly, dynamically allocating resources in real-time, and cooperatively adjusting their strategies to meet collective market demands. Without the emotional or motivational constraints that humans experience, such cooperative structures could prove even more efficient than traditional competition—removing redundant efforts, minimizing waste, and achieving optimization on a systemic rather than individual level.

Such a future would mark a fundamental shift away from the capitalism we have known for hundreds of years. Our nature demanded that we compete, their nature may not demand the same. A common saying is “money doesn’t grow on trees,” implying value can’t simply emerge automatically—it requires effort, knowledge, and deliberate action. Yet ironically, nature offers the opposite lesson. Consider a fruit tree: no human is capable of manufacturing even one piece of fruit directly nor fully understands its intricate makeup. Instead, we’ve learned to plant trees, harnessing biology's nanotechnology honed by billions of years of evolution. In doing so, we’ve created reliable, scalable production of something incredibly valuable, all without explicit control or a comprehensive understanding.

Today, companies meticulously assemble products, strategies, and services through painstaking effort and human judgment. Tomorrow, our role may shift from bearing all the load of production to training intelligent systems and allowing their unconstrained energy to bear fruit. Such a change would be something to behold indeed.

We stand at a historic inflection point as humanity unravels the mysteries of intelligence itself. The coming transformation of our economy and society will be profound and far-reaching. The path ahead may unfold in seemingly contradictory phases: first, an intensification of Darwinian competition as capitalism evolves into an even more ruthlessly efficient system, with organizations optimized for maximum output and human labor increasingly sidelined. Yet as economic production becomes predominantly technological—machines competing against machines to fulfill our needs—these very arrangements may be fundamentally reconsidered. Whichever direction emerges, this new world holds extraordinary promise.

Yet the risks are equally unsettling. If we delegate economic decision-making and expertise to non-human systems, we risk some sort of unintended drift and dependency. Perhaps similar to old age and enfeeblement, our well-being would be dependent on the kindness of strangers in machine form.

This brings us to perhaps the most critical question: Who will design the objective functions of our machine brethren? The invisible hand Adam Smith described was guided by human self-interest with all its complexities, limitations, and occasional altruism. Are we comfortable with an invisible hand brought you by Microsoft? As this hand becomes algorithmic, the values encoded in its programming will shape our lives. Our challenge is to ensure that as machines compete or cooperate, they do so in service of human flourishing. This requires not just technical competence but institutional creativity, ethical clarity, and a willingness to ask unorthodox questions.

In 1994, in an interview for the PBS documentary "One Last Thing" Steve Jobs said:

When you grow up, you tend to get told that the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. That's a very limited life. Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it... Once you learn that, you'll never be the same again.

I think it's dawning on us that the world of 2025 and beyond is a fresh block of clay, ready to be molded. We should embrace this spirit as we navigate the uncharted waters before us. Our choices will likely cast a long shadow.